Dear Barbara,

The moment the plane lands in Chisinau, the Moldovan passengers start clapping. It’s as if something remarkable just happened. I then think of the Greeks clapping on landings and also of the Italians of the south. I always try to observe the clappers. All these landings are returns to homelands that once suffered and unfortunately broke down. For such regions, I -probably falsely- assume that clapping is a confirmation that a devastated land stood again in its feet, exactly like a human after a flight.

It’s freezing when I exit the plane, and I see snow everywhere. The queue towards the passport check moves like a melancholic snail. We snake along the cold corridor, and I think of the movie I watched last night. I always watch a movie before traveling: it’s the only way to comfort my excitement. Last night I watched Three billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri. For two hours, I followed some unsympathetic characters. I even thought of skipping it.

Now, in this long queue at the airport of Chisinau, the movie becomes somehow relevant. I don’t know if I stand out of the crowd, but a guard comes towards me. He groans, he walks around me, and for a few seconds, I feel monitored. The movie, the clappers, the guard. For some odd reason, it seems there’s only one way for countries to stand again on their feet: suspicion.

It’s finally my turn to show the passport. The woman behind the desk -pretty face, rough manners- asks questions that sometimes I can reply (“How long will you stay?”), but other times, I fail to because they’re the core of every journey (“Why did you decide to visit?”). Soon, the bureaucratic interview comes to an end. She then says:

“Have a nice departure.”

“Uhm,” it’s the best I can say, “I just arrived.”

“No, okay.” She then smiles for the first time and understands that she got confused. “Don’t leave Chisinau just yet.”

In downtown Chisinau, in the shadow of huge buildings

No street in downtown Chisinau seems too far away from poverty. When entering the city, you have to cross a cluster of huge apartment blocks dating back to soviet times. These eerie buildings of brutalist architecture have more than twenty floors and sprawl for hundreds of meters on both sides of the wide boulevard. Throughout my stay in Chisinau, I try to visit these blocks at different times of the day. I want to see how life unfolds inside them.

At night, the apartments’ big windows, the ones belonging to the living room or the kitchen, are lit by one light on the roof. The bedrooms are dark. Observing these apartment blocks from afar, one can see a vertical column of light connecting all the kitchens and living rooms. It feels as if the whole domestic life of Chișinău starts and finishes under a pale roof light. For Westerners, the high cost of electricity is a misfortune. But here, in former Eastern Europe, it becomes an existential element.

As for the city center of Chisinau, one can imagine it as the area where the houses have just one or two floors. That’s where most of the shops are located and also the area where you can find public offices and museums. On the opposite side of the Government House of Moldova and straight at Stefan cel Mare Boulevard, the city’s main avenue, I see the Triumphal Arch. The so-called Arcul de Triumf of Chisinau commemorates Russians’ win against the Turks in the 1828-29 war. Together with the monument of Stephen the Great that lies in the nearby park and the Nativity Cathedral behind the Arch, they give an almost heroic atmosphere to the area.

The street market of Chisinau and the spring that’s yet to come

A couple of meters after the town hall, the street vendors sell old things just outside McDonald’s. Soviet tools, old cameras, and talismans, lots of colorful talismans. I fail to negotiate a fair price for some bizarre world war medal: the language barrier prevents me from the most basic trade processes.

I keep walking down the street with my Ricoh in hand. All I want to do this afternoon is stare at the houses. Most of them are dilapidated from time and weather, but you feel a relative geniality when you see their smoking chimneys. As I slowly discover, the locals have a roughness in their manners, but they’re not rude at all. Dressed in their thick coats, they resemble human apartment blocks that winters will always exhaust them, but they’ll never defeat them.

I visit Valea Morilor Park, but I can’t really enjoy it. The wind is strong and the cold severe. I only have a short walk there, and I have the feeling that this is a miniature mix of two places I visited before. It actually reminds me of both the Potemkin Stairs in Odessa and the Cascade Complex in Yerevan. But soon I leave it behind, and I search for public transport. Under these weather conditions, I must constantly search for heated places.

Both the buses and marshrutkas are on time. One should always spend time at bus stops: it’s a silent way to interfere with local life. The people embark and disembark and search for their way through the compact city of Chișinău. Half a million people live under the sky of Moldova’s capital. Big melancholic eyes, wrinkly faces, old-fashioned clothes, and an indolent way to move around: all these things portray the local society’s image.

It’s through these faces that one can assess the historical weight. The spring didn’t arrive yet. At times, Chisinau looks like a city that exited a year-long war with remarkable dignity.

At the National Museum of History of Moldova

Chisinau’s National Museum of History is housed in a building whose interior reminds me of a mausoleum. It has thousands of items on display and all of them deal with life in Moldova. The rooms are vast and remind me of airport corridors. It seems that only women are working in the museum, and this freezing morning, I’m the only guest. For security reasons, the ladies seem to deliver me from one to the other. There’s not a single second that I’m alone. The cold within the museum is severe, and it feels even colder than in the city. The women wear thick coats, and I must remain in their orbit.

Every time I attempt to enter another hall, the next lady responsible for me speeds up. She literally runs towards the next door and searches mechanically for the electricity switch. She turns on the lights and then asks me for my ticket. When she validates it with her eyes, she nods. It’s okay to enter now. After I walk around for a couple of minutes, I leave the room behind. Then, the woman turns off the lights, closes the door, and sits on her chair.

This happens again and again. These middle-aged ladies that run from switch to switch and sit on frozen chairs resemble human photocells. Even though they work for the museum, they deal more with electricity and less with Moldovan History. But one day, History will probably include them in its pages. That’s not just because there’s poetry in their moves. It’s mainly because they are witnesses of a transitional era.

Tired musicians and a shovel

Some tired musicians leave their instruments aside after every song. Each break lasts approximately ten minutes. La Taifas is a basement restaurant in the center of Chisinau, promising an original experience. It employs middle-aged waiters: their hair is wavy, their shirts white. In the entrance, an older man requests the visitors’ coats. It’s a character that aged in front of this improvised wardrobe and offers welcoming drinks in glasses made of clay. “If you don’t drink this wine, you can’t enter the restaurant,” he says jokingly. “It’s a strict Moldovan tradition.”

The musicians sit at the first table. They have violins and guitars, and their tablets are connected to the Internet. They’re searching for songs. Their repertoire varies: from 70s rock to 80s pop. Whenever they feel ready for the next song, they leave the tablet aside and stand. Then, they perform the song, and when they finish, they sit down again. It’s time for that ten-minute break again.

The fireplace is lit; it’s hard to bear the -18 C of that night. Since the service is slow and smoking is not allowed, I step out for a cigarette. When I take my coat from the wardrobe, I see a man next to the heater warming his hands. The moment he sees me, he jumps up like a spring. He grabs a shovel and nods me to wait.

He cleans every step carefully, and when he’s done, he nods me to go through. While I’m outside smoking, the man stands beneath a street light and looks somewhere far away. He tries to warm up his frozen hands with his breath. When I’m ready with the cigarette, he nods again. I have to wait until he finishes shoveling the ice.

The man does this thing for every client entering and exiting the restaurant. It is a tough job that’s also underpaid. The only pleasure that he gets is probably these short pauses next to the heater, on the edge of the wardrobe, where he warms his cold hands.

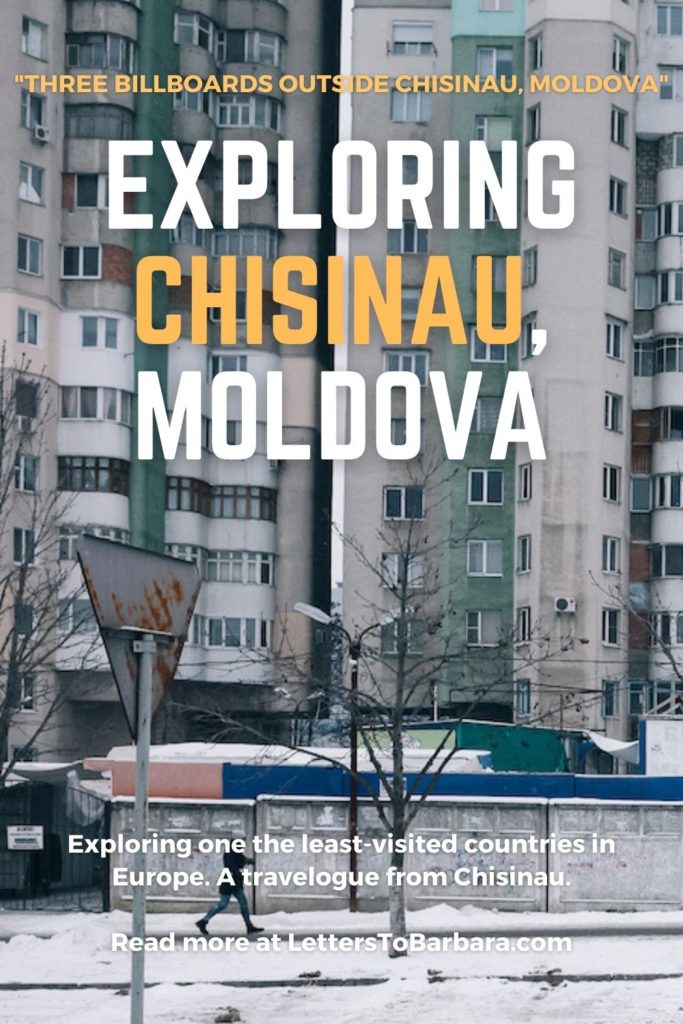

Three billboards outside Chisinau, Moldova

One morning I leave Chisinau for the day, and I visit Transnistria. Another day, I decide to visit the underground wine cellars of Cricova. And another day, I decide to get lost and have a day trip in the Moldovan wilderness. These three escapes have almost nothing in common. Almost. The only thing that connects them is some empty billboards.

The movie I watched before traveling to Chisinau might have a larger impact than I thought. In Chisinau, I remember the 80s in Greece. Billboards were a thing back then, but what you could mainly see were layers of printed ads. Nobody cared to remove them. After years of advertising, the layers were so thick that the billboards looked fat. But here in Chisinau, the billboards are empty. They are white, almost compatible with the snow that covers the city.

In each of my three-day trips from Chisinau, I keep seeing billboards. And the moment I leave the city borders behind, there’s always one last billboard. I try to see if there’s graffiti or something written on them. A message, maybe. But there’s nothing. And every time the city is about to stay behind, I know that the city’s borders are not marked on a map. It’s just a billboard -and nothing is pointing towards somewhere, like in that movie.

“Advertisement, or the lack of it, seems to be the new border,” I think pompously the last night. I’m having dinner at my favorite restaurant in Chisinau. Its name is Propaganda. A warm interior where the few tourists that visit Chisinau mingle with the locals. Wine, chatter, delicious food from the former Soviet Union -what more can I ask for?

The allegories of Chisinau

It’s five o’clock in the morning, and I must check out from the wonderful Regency Hotel. The employees are sleepy, and so am I. They prepared a lunch box for me, and I’m grateful beyond words. Then, I say goodbye, and I’m off to the airport.

The frozen highway is deserted. The only lights I can see belong to two-three scattered gas stations in the middle of nowhere. Despite my urge to listen to some music, I don’t turn the radio on. I prefer to have a pure experience without music, just listening to the tires struggling on the icy street.

No doubt, it’s the coldest dawn I ever experienced. It’s -23 C, and when I leave the car, I have a small distance to cover on foot. These 100 meters feel like a marathon. The moment I enter Chisinau’s airport, the only thing I have in mind is to buy a cup of coffee. No, I’m not desperate for coffee. I just need something to warm up my hands, and a hot cup of anything sounds ideal. I spend my last thirty lei and stay next to the heater like that man shoveling the snow at Taifas.

It’s one of these circular journeys, where the last impression is actually the first one. I can almost hear the words of that woman on my arrival: “don’t leave Chisinau just yet.” And the truth is that I don’t want to leave. As if Chisinau is the Catania of the East, I want to stay here and explore it further. Its charm doesn’t unfold straight away. It takes time, patience, and a bit of courage. But as the plane takes off, I see downtown Chisinau’s sleepy roofs under a blue veil.

And then I see the fields, rutted plots of land covered in snow. Sleepy as I am, I wonder if these aren’t fields but faces standing on a bus stop. And, subsequently, I can only wonder if these faces will ever leave Chisinau behind or if they’ll stay in the country to fight for a brighter future.

Love,

George

More travelogues from Eastern Europe: Kyiv, Bucharest, Minsk

The best hotel deals in Chisinau

Pin it for later

Did you enjoy reading this Chisinau travelogue? Let me know what you think in the comments.

Last Updated on May 15, 2021 by George Pavlopoulos

Hi, thanks first of all for sharing this experience, you made me travel with you.and yes agreed with that message”Departure not yet”lol..being native from Moldova,can confirm that it’s like you wrote,you want to go away from there and same time,curious to discover other this place. MULTUMESC

Hello Valia!

Thanks a lot for your kind words. Yes, this moment at the airport was hilarious. For me, Chisinau was a great (positive) surprise. Despite the insanely cold weather of late February, I saw a fascinating city. I wish I could stay longer. Moldova is definitely a country to explore further. Since you are a local, could you share any tips for other places of interest in Moldova? I’d definitely like to visit again in the future. Sad to hear that the “Propaganda” restaurant in Chisinau closed forever; they couldn’t overcome the financial loss of the pandemic. So many lovely memories…

Take care,

George

Thanks George, I’ve been reading your posts for a while now and it was pleasant and unexpected to see this nice one about Chișinău, my hometown, also w/ a curious connection to a movie I did like a lot. I’m also a writer/photographer, also living in Berlin και μιλάω λίγο ελληνικά. Όταν θέλεις, μπορούμε να πάρουμε ένα μπύρα κάποτε.

Hello Teodor,

Thank you so much for your kind comment. Chisinau has a special place in my heart, and I would love to revisit it soon. I think there are so many things I haven’t seen in Moldova.

Sure, let’s catch up in Berlin in autumn -I’m currently in Athens for the summer. It’s always nice to meet fellow writers/photographers. Μιλάς πολύ καλά ελληνικά!

Χαιρετισμούς!

George