Dear Barbara,

Tbilisi feels totally vintage. In some streets, I think I have a déjà vu: it reminds me of Athens in the early ’90s. The roads, the infrastructure, the sparkly look in the eyes. There is ambition in Tbilisi, and at the same time, there is an old-fashioned feeling.

There seems to be an end of an era here in Georgia. A huge behavioral gap between generations is somehow visible. It’s not only the clothes, although fashion always narrates (and sometimes dictates) a change of habits. It’s also the way the people walk down the streets. The older generation, the ones above sixty, remind me of the older guys in Greece before the changing of times made them look obsolete: one-dimensional bodies, odd haircuts accompanied by a forgotten body language. The youngsters, on the other hand, seem to communicate on another wavelength. They look to me totally European, the shape of their bodies is delicate, and the tone of their voice softer.

Whenever the young ones set both the rules and habits, the times are changing. I saw it happening in Athens, I observe it in Berlin. It is natural, and some people might mourn for it in Tbilisi. This is a side effect of globalization, and as such, it will create controversy. The clash of habits is an underground, multidirectional stream that reshapes society. Since Tbilisi is booming in terms of economy, the older generation will lose that battle. I hope at least that they won’t slip into oblivion.

If Rustaveli was still around in Tbilisi

Arriving at 5 am is always cruel, but that’s the case of the international flights in Tbilisi: they usually arrive very late. I sleep less than four hours, and after a quick breakfast in the hotel, I hit the streets.

It’s cloudy, and there are a few raindrops every now and then. But it never really rains. I take the Giorgi Leonidze Street, and a couple of blocks later, I arrive at the flamboyant Freedom Square. Equally impressive is the historical impact of the square. It’s the spot where the Tbilisi Bank robbery took place in 1907 when the Bolsheviks stole a bank cash shipment in order to fund revolutionary activities. In that very spot took place in 2003, the Rose Revolution, which marked the pro-Western turn of Georgia. Last but not least, Freedom Square is the place that Vladimir Arutyunian tried to assassinate George W. Bush in 2005 by throwing a grenade at him; the grenade never detonated though, otherwise, Arutyunian would have probably been a modern-day Lee Harvey Oswald.

There is always traffic in the Square. Six streets start from there, the most famous one being the Rustaveli Avenue. Named after the National poet of Georgia, this is the street that I spend most of the time while I’m here. It is a melting pot of cultures, of generations, of hopes. There are loads of people walking in front of architectural landmarks. An avenue named after a poet seems right to dictate a capital’s dynamic.

But what keeps me going this morning is the smell from the bakeries. I am so tired that I promise to myself to stop walking when the scent from the cheese-bread vanishes. But this never happens, and I keep on walking the Rustaveli Avenue until the end. In the entrances of the older buildings, where usually there is an arched passage driving to inner yards, the street vendors sell fruits, old stuff, and popcorn. These passages are dark, the vendors are old, and the products colorful. The colors appear out of the darkness, like still life paintings by Juan Sánchez Cotán.

I’m pretty sure that if Rustaveli was still alive, he would have had enough material for writing. But, I’ll have to be fair: it’s his aura that gives the avenue all that life.

The welcoming soul of Tbilisi

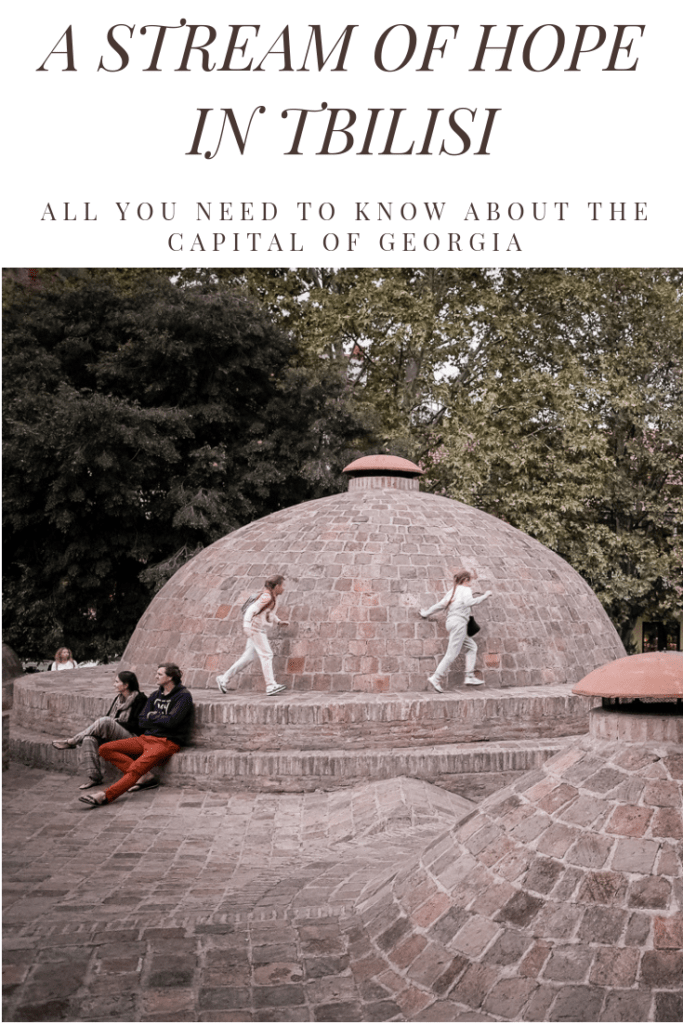

Empires have sandwiched Georgia for centuries, and still, the country exists and has a remarkable variety. As I walk around the Old Town, which stretches along the Mtkvari river, I end up at the sulfur baths of the Abanotubani district. Amid the baths, there is the Jumah Mosque, an old temple of the city, in which something unexpected happens: Sunnis and Shiites pray side by side. This happened back in 1951 because the Communists demolished the Blue Mosque, and thus, the Shia community had nowhere to go. The Sunnis opened the Blue Mosque’s door to them, and today is one of the very few mosques around the world that this happens.

Further down the road, I stop at The Leaning Clock Tower of Tbilisi, which is located next (or should I better say attached?) to the Rezo Gabriadze Puppet Theater. The Georgian puppeteer Rezo Gabriadze created this unique clock by using materials from abandoned buildings, and it is by far the most playful element of the Old Town.

Architecture and religion can both be stubborn and conservative at times, but in Tbilisi, there seems to be a different narrative. I sit on a bench next to the sulfur baths, and I try to evaluate the puppeteer’s tower and the mosque that both sects can pray. Despite the powerful Church, there seems to be a vein of great tolerance in the city, a vein that has to be shielded in the years to come.

Barbara, meet Barbare

Your name is significant in Tbilisi, Barbara. In the 19th century, there was a woman called Barbare in Georgia. She was a princess and an author, and she is assumed as the first feminist of the country. From what people tell me, she has also written a cookbook, and this became some sort of a culinary gospel for the country. Even renowned contemporary chefs use her book when it comes to Georgian cuisine.

And it gets even better: there is a restaurant on the other side of the river that serves food after Barbare’s cookbook. Its name is Barbarestan and, guess what, I’m sitting here as I type these words. I know that you are curious to find out what I ordered and how it looks like. Well, the interior is relatively dark, and the wine list is impressive. I have just ordered a bowl of Imeretian mushroom soup, but I didn’t make up my mind about the main dish yet. I’ll figure it out while drinking the excellent red wine they served me.

The waiter is helpful. I drink wine, and I chat with him. I’m pretty convinced now: I’ll order the Chicken Borano with spinach and matsoni sauce.

A bad dream in Tbilisi

I have a night full of nightmares, and I wake up with agony and grief. It’s a bad dream about my brother. It takes me quite a while to recover. Traveling makes us vulnerable, Barbara, we worry about things on a larger scale. All of our fears develop in a different way when we are on the road: they maximize due to the distance. We worry more, we love more, we miss more. But at least we enjoy more, too.

Later this day, I meet Luca, and we embark on a journey across Georgia. We leave Tbilisi early in the morning, but we keep on talking about the capital all day long. I’m going to talk to you in another letter about the place that capitalizes my Georgia experience.

Late in the afternoon, we end up at Luca’s hometown somewhere in the province. His grandparents live there together with his uncle and his family. The people are friendly beyond words. They invite me to their house without second thoughts, and they prepare a meal that seems to be the most delicious meal of the year. It’s not salt and paper that makes it tasty; it’s kindness. There is homemade bread, there is an insanely tasty cheese, there is wine, refreshments, and a plate of potatoes. And a bean soup that convinces me, a guy who hates beans, to ask for a second portion.

The grandpa takes the seat on the top of the table. This is a tribute to the older generation that reminds me of Greece. The old man wants to know where do I come from. And then he starts a missal, full of blessings for my family and me. He talks about our countries, Georgia and Greece, he talks about our families. Every once in a while, he nods to Lucas: my wine glass is empty, but in every Georgian house, it should remain full at all times. I end up drinking loads of homemade wine, red in color, spicy in taste. The grandpa says I must get married and have 12 kids. I laugh, of course, and then he says that I should revisit Georgia. I promise him that I will.

Next to me, the kids of Lucas’ uncle play some games that I fail to understand. Two young boys, three and nine years old. After that bad nightmare, it’s a joy to watch two brothers having a good time. I think of my brother, I think about the concept of brotherhood. Something breaks inside me, maybe I should blame the wine. Brotherhood, in any concept, is an idea that I appreciate more and more as I grow older.

They don’t listen to us

My last day in Tbilisi coincides with the presidential elections. I have read a little bit about politics in Georgia, and I can hold a conversation for a few minutes. But the reality is always different, and it’s the narrative that defines our perception. I try to talk to as many people as possible about the elections. All of them seem equally dissatisfied with the situation in the country. There is a constant motif in their thoughts: the politicians only care about themselves, not about us. “They don’t listen to us,” they say.

Tbilisi is full of people this Sunday morning. People talk about their hopes and try to forecast the result. Sooner or later, you can hear people arguing. Georgia, pretty much like Greece, is a country with a long history in wars. I’ve never seen a country that was often in wars that don’t have disunity in its interior. Clash is part of the collective DNA.

I wait to listen to the first results in a cafe in Tbilisi. I’m sitting outside, and the weather is pleasant. The policemen are vigilant. Rustaveli Avenue is full of people. Tbilisi is booming, and in a few years, the city will change a lot, much more than any other city. But it’s almost time for the first results.

One last cigarette in Tbilisi

My flight leaves extremely early. It became almost a tradition not to sleep the night before an early morning flight. I sit on the balcony, and I smoke. It’s Sunday, and it’s quiet. All the windows are dark. The wind is mild, it is a beautiful autumn night. Behind the trees, I see the tower of the television. It’s me and this building right now, everybody else seems to be asleep.

I’m probably broadcasting on a different wavelength from the TV Tower. I’m in a rough but tender city, full of sulphuric hot springs. There is potential here. And wherever there is potential, there is hope for the future, too.

Thinking of you,

George

More about Tbilisi: A monk above the clouds & Chiatura, a modern dystopia? & Things to do in the city

Pin it for later

Please share, tweet, and pin if you enjoyed reading A stream of hope in Tbilisi. Your support keeps this website running and all the info up-to-date. 🙂

Last Updated on May 19, 2020 by George Pavlopoulos