Dear Barbara,

It’s late spring in Amorgos. The car huffs and puffs uphill on the fierce road over the cliff. The damaged asphalt connects two ports, but there is a question beyond usability. Who has envisioned this route? Was it a bureaucrat or a geographer?

It is a route that ascends slowly, reaches the top, and then slowly descends to the opposite slope. In a sense, the road is reminiscent of the berms surrounding Amorgos, these stone terraces stopping the violence of the weather. They look like giant steps: one can even imagine those giants descending with heavy steps to cool off in the summers at sea.

Building roads on a rocky island has a heroic and, at the same time, abominable beat: it is like making life easier by incorporating urban parameters. However, the fissure of the landscape on Amorgos seems like an abstract compensation fee.

On one side of the road, you can see Anafi, Astypalaia, and Santorini; on the other, Donousa, Schinoussa, Naxos, and Koufonisia. It is no longer a road but a geography lesson on a blue board.

At the ports of Amorgos

The landscape looks tame in Katapola and Aegiali, the island’s two oval ports. Ship smoke may have smoothed the slopes and peaks of the surrounding hills. The closer you get to the pier, the more restaurants you see. The last bite before departure somehow seals the life of the ports.

At least the waiters do not have the roughness of Santorini. They appear and disappear silently, like the shadows of winter, and the oval disks they hold look like a tribute to the landscape. They serve baked raki (psimeni raki) in a crowd, temporarily resting before the sun burns their cheekbones.

Life is weighed in Aegiali and Katapola, but the will to breathe by the water has no weight. It is the carefree end of the pandemic suffocation at the beginning of another summer. You have to welcome it happily, whatever that means.

The waiters still bring baked raki. Foreign travelers drink it breathlessly and knock the empty glass noisily on the table. Then, shining like afternoon pebbles, they look for the next stop, the next beach, the next moment where the island will surrender to them selflessly.

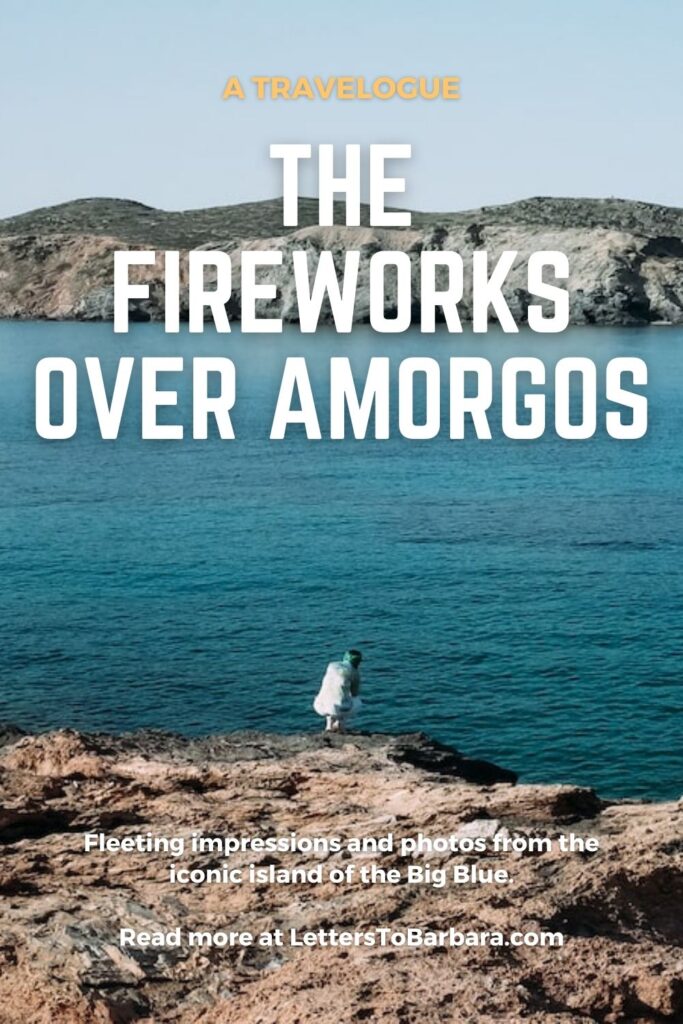

The Kalotaritissa shipwreck in Amorgos

At this time of year, Amorgos has vegetation; the sun has not yet discolored the landscape. Thousands of red and plump poppies live on the slopes in a sea of stone.

As the road slides towards Kalotaritissa, a herd of goats appears running on the asphalt. Behind them, down at the beach, a shipwreck, like a nightmare or a parable. The query about the unusual sight translates into a short hike. It does not take more than a quarter to get there.

The goats are ahead, and if one succumbs to metaphysics, he imagines that they are showing the way. However, a moment later, they disappear from eyesight and never reappear. But the path they have shown elusively is the one that hikers ultimately follow.

The ship sank forty years ago amid a storm. No one has been killed, but year after year, the boat tilts. Its rust drains into the water, and its stern looks toward the sunset. Human accidents are often a magnet; the beach in front of the half-sunken ship is full of rubbish.

Voices are heard back in the middle of the path. Some other travelers have been fascinated by the wreck. The beach is small, and there is not enough space for everyone. A goat jumps out of nowhere and makes its way back. It looks like an usher that one should follow: no one must stay too long in front of adversities.

Towards the Amorgos Hozoviotissa Monastery

The path to Hozoviotissa Monastery begins from the slope at the edge of Chora. Then, a small challenge: three hundred steps to reach it. The monastery is not visible from any part of the island, only from the sea. The whitewashed building is a sculpture carved into that rock. It spreads over eight floors, and its entrance is narrow.

The wandering ends in a window overlooking the Aegean. After a short chat, the cheerful monk serves cold water and sweets and follows a tour between sacred icons and photos of archbishops. Finally, the exit to the terrace, where a carpet dries in the sun. It’s time to leave.

A little further down, the beach of Agia Anna, where it is said that the icon of Panagia Hozoviotissa arrived a thousand years ago. It is also the place where the film that made Amorgos famous was shot. But if you expect a wide beach, you will be disappointed. It is so tiny that it would hardly fit in a Cycladic house.

To be precise, it would only fit one Cycladic room. But, at least it would have a view of the big blue.

Tholaria, Amorgos

Afternoon at Tholaria. It is probably the whitest village in the entire Aegean Sea. The presence of people here is abstract. Not a single soul is walking on the street, but the laundry is spread in the yards. A cat here, another one there, and two stunned tourists wiped out by the sun.

On the last street of the village, where the last step becomes a veranda overlooking the still green slope, a crowd of children plays. They shout, they run, they get lost. Yet, the echo of insouciance and a ball that jumps on the stone slabs remains: its tempo is so constant that one wonders if it obeys gravity.

Blue shutters open after a while. This is undoubtedly a warning: it is only a matter of time before a retiree raises his voice.

Chora, Amorgos

The small square of Chora is dressed from the chairs of Kath’odon, which serves homemade food two streets behind the church. It is basically a theater because one can watch the passers-by and steal a couple of words or even half a picture.

A diplomat narrates travel stories; some Americans try to figure out what baked raki is; the cheerful owner serves dishes with cheese. Then, as time passes, the people walk down the narrow streets and move gloomily and formally towards the church.

It is the night of Holy Saturday, half an hour before the Resurrection. The oregano scattered in the streets from yesterday’s epitaph still smells. Under the rare trees of the square, the wine flows. Just a few people leave the tavern to go to church. It’s as if participating in the night seems already enough.

Easter in Amorgos

At midnight, the first firecrackers sound. Conversations are interrupted, and the eyes turn right and left like periscopes. Then, the fireworks open like an umbrella in the sky and hang for a dense moment in the air among bright stars.

A young woman dressed in a polka-dot dress crosses the small square. She looks like she jumped out of a Fellini’s frame: she slowly walks and ignores what is happening around her. She’s smiling, and the fireworks are multiplying. Despite the explosion of colors, everything becomes black and white. At every step, she seems to leave something behind, not something personal, but something we all experienced.

No one wakes up from lethargy alone. We all need someone to wake us up—and such persons are rarely experts. A random image, such as this black-and-white scene in Amorgos, is often enough. A disease that has gripped the world seems to come to a social end this Holy Saturday in Amorgos, from the footsteps of a woman who disappears behind the white walls.

All that remains is the light that thrives on the sea and becomes a story of stone and decision. Everything is about the next day, the next night, and the ill-advised question of whether we are ever really alive. Soon, when the fireworks stop, and the bells chime, people with candles walk to Chora. Quiet and diligent, Amorgos swallows them and sends them to festive tables.

In the end, no one needs to remember. It’s just enough to forget. And just like water, every misfortune flows away.

Love,

George

More about Amorgos: The ultimate Amorgos travel guide

Pin it for later

Sharing is caring. Share this Amorgos travelogue with your friends.

Last Updated on October 2, 2024 by George Pavlopoulos