The road to Mettingen runs through the fields. It is a sunny day, and I’m headed toward a museum less than half an hour outside of Osnabrück. I will be attending the opening of the “Faith” exhibition at the Draiflessen Collection (“Glaube” in German). I’ve never been there before, and as I see the small town of Mettingen unfolding, I roll down the window. There is no traffic here, and there is only a man walking a dog, a woman returning from the bakery, and a couple taking a stroll. I find those street scenes interesting: daily life is an exhibition in small towns.

And then, after a cluster of residential houses, the car stops outside of the Draiflessen Collection. It’s a building made of concrete and glass surfaces and stands there as a family’s tribute to its birthplace. This is the private museum of the Brenninkmeijer family, which has a long tradition in the business world that dates back to the 17th and 18th centuries. By establishing a museum in Mettingen, the family paid tribute to their Westphalian roots. This is a non-profit museum, and, of course, it’s open to the public.

I arrive at the museum shortly before the speeches. Τhe President, the Director, and the Curator inform the audience about the exhibition “Faith” and its purpose. This is actually the first part of a trilogy about the cornerstone Christian virtues: Faith, Love, and Hope (Glaube, Liebe, Hoffnung, in German). Less than half an hour later, the Director of the Museum announces the exhibition’s opening. And then the doors open, and the tour of the “Faith” exhibition at Draiflessen Collection starts.

“Faith” exhibition at Draiflessen Collection

I always prefer more compact exhibitions. Touring through rooms packed with numerous art pieces somehow distracts me and makes me tired. The “Faith” exhibition at Draiflessen Collection is exactly my kind of exhibition: a fine selection of 8 works of art. The museum’s interior is carefully arranged, and there is breathing space for each artwork. Quite obviously, all of them deal with the concept of Faith.

After walking a couple of stairs, the visitors initially stand in front of a wall projection. There are words connected to faith running on the screen. All those scattered words serve as a prelude to the exhibition itself, behind that wall projection.

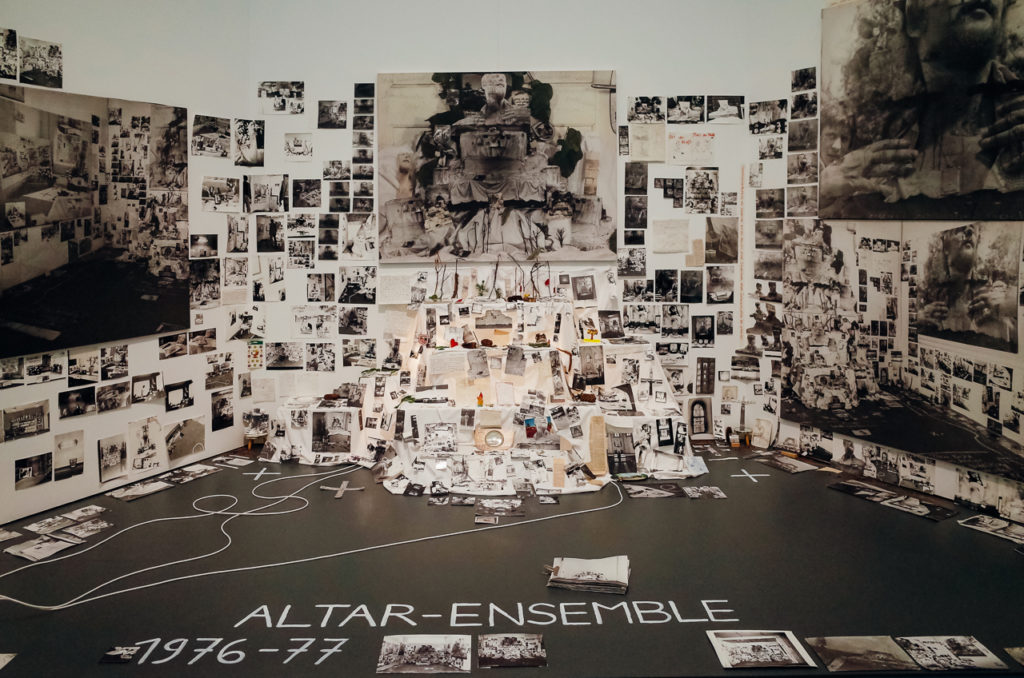

Altar-ensemble (1976-77), by Anna Oppermann

Anna Oppermann created well-arranged chaos in her Altar-ensemble mixed-media installation. This impressive work is a highlight of the “Faith” exhibition at the Draiflessen Collection. Despite looking like a jungle, the photographs do have a strong connection. In addition, there are tags with solid references to faith, like “New Inwardness, Christ on the Cross, Paternal Authority and a garden gnome.”

Ironically enough, the order that Oppermann seemed to choose is somehow the absence of a concrete order. And yet, the result is impressive and eye-catching. Despite its strong background in terms of faith, I also perceived it as a journey down memory lane.

Der Engel und Sein Schatten (1974), by Michael Buthe

Next to the Altar-ensemble, the visitor comes across Michael Buthe’s work, called The Angel and his Shadow. Two symmetrical figures flow towards each other. There is tension between them from the very first moment. The colors are vibrant -or even fierce- and there seems to be a clash between them.

The tension is real, and -ironically, the two figures depend on each other once again. Depicting a battle as old as the world, Buthe’s work magnetized me at once. I returned several times to it, and it’s -probably on purpose- the final artwork that one sees before leaving behind the “Faith” exhibition.

Untitled (1966-67), by Paul Thek

American artist Paul Thek pays tribute to the burial rituals of ancient civilizations. A death mask on display sinks into a three-layered pyramid, replicated inverted above the mask itself. This is a complex work of art, where the tongue stands out of the mouth and has a ring piercing. The artist claimed that the inspiration behind the sculpture was the theme of the Crucifixion.

Death, what remains, and what is yet to come are all essential elements of religion. In my opinion, Paul Thek’s artwork was the most shocking of the whole exhibition.

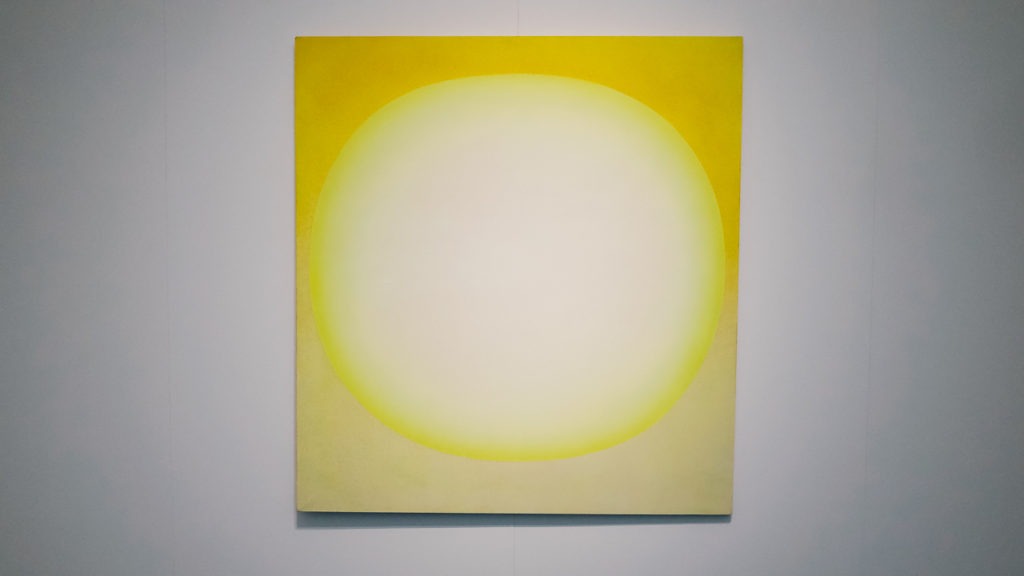

OE 477/ 67 Gerundetes Gelb (1967), by Rupprecht Geiger

Exactly after Paul Thek reflects upon what is yet to come, I stand in front of another existential question: what is there left to believe in? This is the question that Rupprecht Geiger seems to address to the audience with the 67 Rounded Yellow painting. This large oil on canvas painting has a white radiating center, but it further turns into yellow variations when it expands.

For most people (myself included), this is definitely an abstract work of art. However, it seems to have a solid sentimental impact on the viewer, producing a broad spectrum of emotions -anger, joy, tranquility, and envy.

Untitled (McDonald’s) (2004), by Angela Strassheim

A family of six is sitting around a table at McDonald’s. They are all holding hands and saying grace. At first, it seems like a typical scene. But after paying attention to the photograph, there is one person, the girl on the right, that seems disconnected. Why is she really disconnected, though? There are specific questions in Strassheim’s photo: the freedom of choice, the meaning of faith, and the right to believe or not.

After the exhibition, I had the chance to talk to Angela Strassheim; she also attended the opening of the “Faith” exhibition at the Draiflessen Collection. She told me that the photo was staged, but it was based on a street scene she observed. It also reminded her of her own memories, and hence decided to recreate the scene.

When Faith moves mountains, Lima, Peru, April 11 (2002), by Francis Alÿs

I found the project by Francis Alÿs impressive. Moving a dune in the outskirts of Lima sounds utterly heroic. On April 11, 2002, five hundred volunteers shifted by several centimeters a dune. The Belgian artist documented the project with photos and video, and all of them occupy a large space at the exhibition hall.

This is not just about effort; it’s also about community, collective work, and deep faith — a project of biblical substance for sure.

The empty cross (1939), by Louis Soutter

Dancing figures around a cross. But the cross is empty, and the whole scene becomes introverted when one realizes that. The dancing figures are, in reality, just shadows. Everything happens in front of the viewer’s eyes, yet there is not much to see. It seems like a self-referential painting, but still, it presents a powerful image and a cornerstone motif.

Soutter’s painting is about death and redemption. But also, it seems like a painting about pain and suffering.

38 Pieces in the form of 19 signs for tables and 25 letters from the words “Once in a lifetime” (1981), by Harald Klingelhöller

The sculpture with the long title has a poetic substance. Signs and letters made of cardboard lean against a wall. They are all stacked together in -what initially seems- no particular order. Klingelhöller’s sculpture probably questions our perception of the world that surrounds us. It also reminds us that content and form might not always work together in harmony.

The artist himself undermines the surface of our perception and requests the viewer to re-evaluate. It might be confusing, yes, but it’s also liberating.

“Faith” exhibition at Draiflessen Collection: An Epilogue

Not that long ago, I expressed my complaints about the Emil Nolde exhibition at Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin; I found it too big and slightly out of focus.

On the contrary, the “Faith” Exhibition at Draiflessen Collection impressed me. This is a compact exhibition that delivers its message straight to the point. The fact that it takes place way off Germany’s artistic center gives an extra value to the experience.

One thing that didn’t find its place in the previous section is the Audio-Station of the exhibition. The curators installed an informative section at the very end of the hall, straight behind the Francis Alÿs project. Get a pair of earphones and hear them sharing various facts about the exhibition in a very laid-back mode.

Mettingen hosts an interesting museum. I’m glad that I had the chance to attend the exhibition’s opening. If you live nearby, don’t miss the opportunity to visit the “Faith” Exhibition at Draiflessen Collection. For those living farther away, maybe it’s time to plan an excursion to Mettingen.

Practical information about the “Faith” exhibition at Draiflessen Collection

- The exhibition “Faith” runs until the 18th of August 2019.

- There is an excellent catalog of the exhibition, so make sure to check it out.

- The exhibition is available in three languages: German, English, and Dutch.

- Opening times: Wednesday to Sunday from 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Also, the first Thursday of every month from 11:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m.

- The museum remains closed on Mondays and Tuesdays.

- Admission fees: regular 9 euros, reduced 6 euros; free admission under 18.

- The museum’s address is Draiflessen Collection, Georgstraße 18, D-49497 Mettingen.

- You can reach the museum by bus. Busline S10 starts from the central station of Osnabrück. Stop at Schultenhof; from there, it’s just a short walk to the Draiflessen Collection.

- For more information, please visit the website of the Draiflessen Collection.

A small photo report from the exhibition

More art: The Art of Replication, Berlinale Guide, Polaroids by Linda McCartney & True Pictures at Sprengel Museum

Buy the camera I use | Book your hotel

Pin it for later

Sharing is caring: share this article about the “Faith” Exhibition at Draiflessen Collection with your friends.

Last Updated on May 18, 2022 by George Pavlopoulos