Dear Barbara,

There was fog on my way to Brest. A thick veil prevented me from seeing the horizon. I could see the nearby trees, but not the distant ones. It felt like a one-dimensional ride most of the time. But, about 40 minutes outside of Brest, all of a sudden, the sun appeared. I could feel some heat in the train, a mixture of warmth and anticipation for the destination. All passengers removed their jackets simultaneously. After three and a half hours of journey from Minsk, everybody seemed ready for Brest.

The first steps in Brest

I’d love to stay at the Hermitage Hotel, a historical establishment with a lot of charm; however, I have chosen the Molodezhnaya Hotel instead, which is far from luxurious. In a way, though, it seems to be more compatible with Brest.

The receptionist is definitely a character. Too bad she doesn’t speak English. She is chubby, has dark hair, and smiles eerily at all times. I can’t figure out if she’s in a good mood or a bad one. She stands behind her desktop and speaks slowly. I have no clue how old this hotel is, but I bet both the building and she, somehow, grow old together.

There is a certain feeling of decay in the hotel: cheap, run-down, and faceless. The walls are full of wrinkles, just like the receptionist’s face. This decay has some sweetness, but I guess it won’t last long.

The hotel is close to the train station, and it’s actually one of the first buildings you see when you arrive in Brest. On the contrary, there seems to be a massive reconstruction at the train station — dozens of workers and dust everywhere. An odd smell is present all around Brest. I have no idea if it’s because of the construction site or due to something else. At times it smells like a barn or as if extreme humidity has sat on the rotten leaves.

Decay and regeneration seem to go hand in hand here. I can’t tell which one is more compatible with Brest.

The “Courage” Statue in Brest

Brest has undoubtedly seen things. However, the major landmark of the city (or even of the whole country) is the fortress. It was built around 1840 and intended to serve as an essential defense point for the Russian Empire. In 1965, the title Hero Fortress was awarded to the Fortress of Brest to commemorate the heroic defense of the soldiers during the first week of the German-Soviet War. It was when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, with the launch of World War II’s Operation Barbarossa.

I walk around the fortress, and the open space makes it even more heroic: one can imagine battles and despair here. The main monument, which probably made me visit Brest, is a thirty-meter-high memorial made of stone. It depicts the head of a Soviet soldier next to a hammer and sickle flag.

As I see it from about 500 meters away, I can feel the enormous symbolic weight that it carries. However, I remain ecstatic when I stand next to it because of the detail. This is definitely one of the most impressive war memorials I’ve ever visited, and its name adds extra meaning to the concept: it’s called “Courage.”

There is a beautiful church inside the complex and several other memorials, but nothing outperforms “Courage.” No matter where I find myself in the complex, I keep on turning my head towards that soldier. His head is facing down, but his eyes don’t.

Contraband Art in the city of heroes

After spending three hours walking around the fortress, I feel that I’ll have to spend another three hours communicating with taxi drivers. Now and then, a taxi will pop by, and then I will go to the driver. I want to take a short ride of fewer than two kilometers, but somehow it seems impossible to understand how much it will cost.

The first driver gives up quickly, the second one tries Google Translate unsuccessfully, the third one shows me his watch, and I wonder if I have to understand something about the time or about our times. I don’t know. The fourth driver seems more patient, but a young couple with a crying daughter wins the ride easily. Finally, it’s the fifth driver that says, “Five rubles,” and I finally get inside.

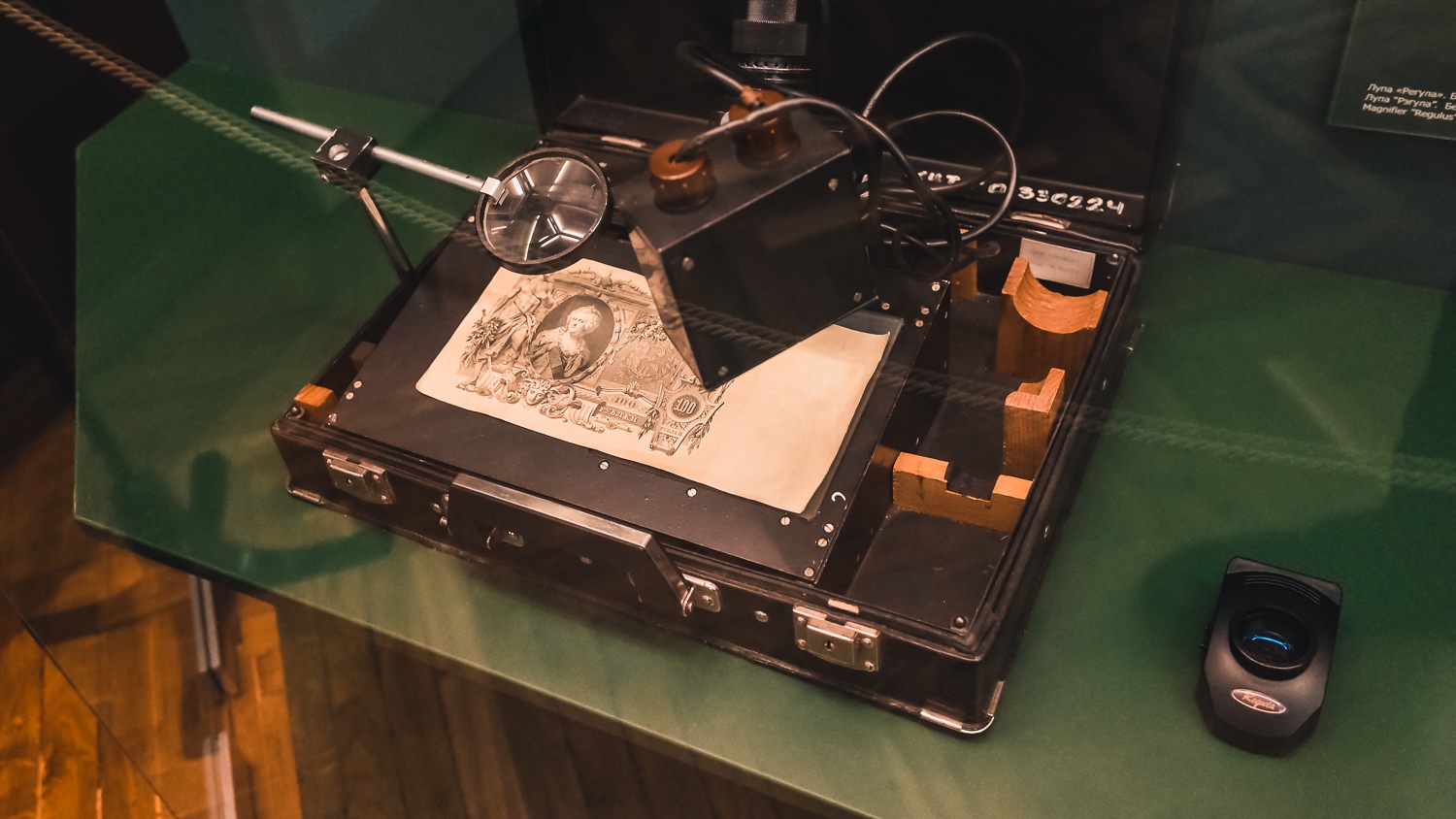

Walking an extra two kilometers is never a problem, but I’ve been in a rush to make it to a bizarre museum: the Museum of Confiscated Art (the direct Russian translation is: Museum of Saved Values). It presents an ever-growing collection of pieces of art that the authorities seized at the last moment from smugglers trying to get them across the border of Poland.

The museum was conceptualized in the ’90s due to political turmoil in Russia -it was the best time for smugglers to get involved in some serious art business. When I arrive at the museum, I see that it’ll be open for just half an hour more. I fail to communicate with the employees again about the ticket’s price. I just leave 5 rubles on the table, and I start walking inside.

The museum justifies its existence because most artifacts are of unknown origin. That said, when the authorities fail to recognize the legal owner, instead of destroying the artifacts, they bring them here. This results in a collection of more than 350 objects of a broad background.

The first floor seems to deal with religious icons of the 16th and 17th centuries and things that have to do with the Church in general. On the second floor, which is more interesting, I see sculptures, paintings, historical dresses, Chinese vases, items of high value that the smugglers couldn’t export.

Despite being unique, the museum doesn’t receive much attention. I’m the only visitor, and all the lights are off. An older woman follows me, and she turns on a lamp every time I enter the next room. Two floors, more than eight rooms, but the whole time the same procedure: lights on, lights off. I take some photos; I read the signs, I walk. And the woman walks behind me. Finally, after visiting the last room, the lights go off. It feels like the final scene of a theater play.

I’m about to walk down the stairs when the lady says something in Russian. She explains it with a smiling face, and she goes on for approximately thirty seconds. Then, she gives me 2 rubles. It’s probably the change from the 5 rubles I left on the table for the ticket. Suddenly, I feel like a smuggler that has to run unnoticed outside of the museum.

It rained all day in Brest

Late at night, I walk Sovetskaya Street. This is one of the most central streets of Brest, and a good part of it is pedestrianized. A few people walk down there; to be honest, I would expect more traffic on a Friday night. I see cafes, bars, and restaurants around me, and suddenly, out of the blue, I think of Jacques Prévert.

I remember his poem “Barbara,” which takes place in Brest. But not Brest in Belarus, the city of Brest in France. This is a beautiful poem about war and grief and, for some reason, seems to accompany me through the night.

It doesn’t rain in Brest today, but that’s what the poem says. I have drunk one single glass of Rioja, and I walk the streets. Maybe it is because of the wine, perhaps because of Prévert, but I think of you, Barbara. I know that you often complain about being based in one city and working in another. I doubt it offers any comfort, but Prévert’s Barbara has no place to return. The poem’s final verses are “A long, long way from Brest / of which there’s nothing left.”

This Brest and its counterpart in France seem to have one thing in common. All the despair, the grief, the absence, and the disappearance have one hidden element: courage. And that’s how I’m going to remember this city on the Belarussian border.

Love,

George

More about Brest: Brest travel guide

*Get my FREE Travel Writing Course*

Buy the camera I use | Book your hotel

Pin it for later

Please share this article with your friends if you enjoyed reading The Heroes of Brest.

Last Updated on December 9, 2021 by George Pavlopoulos