Dear Barbara,

The mountains around Lucerne are covered with snow. There are some legendary peaks around me: the Rigi and the Pilatus, among them, which they belong to the Swiss Alps. This is an expensive city, but I somehow feel privileged. I have a magnificent room straight at the river Reuss, and from there, I can observe the city’s architecture. The room has a balcony, and now and then, I step out, and I have a quick smoke.

For some odd reason, I recall some old dreams of mine. I remember how much I desired once upon a time to live in Paris; I only managed to do it for a couple of months, though. But tonight in Lucerne, I also remember that I wanted to have a flat overlooking the Seine in Paris. This never happened, of course, due to extreme cost, but sometimes there comes a time that dreams transmute themselves into something different. Tonight, a tiny part of that dream comes true: I have a temporary room straight at the river, and I look at the Alps and the bridges of Lucerne.

The bridges of Lucerne

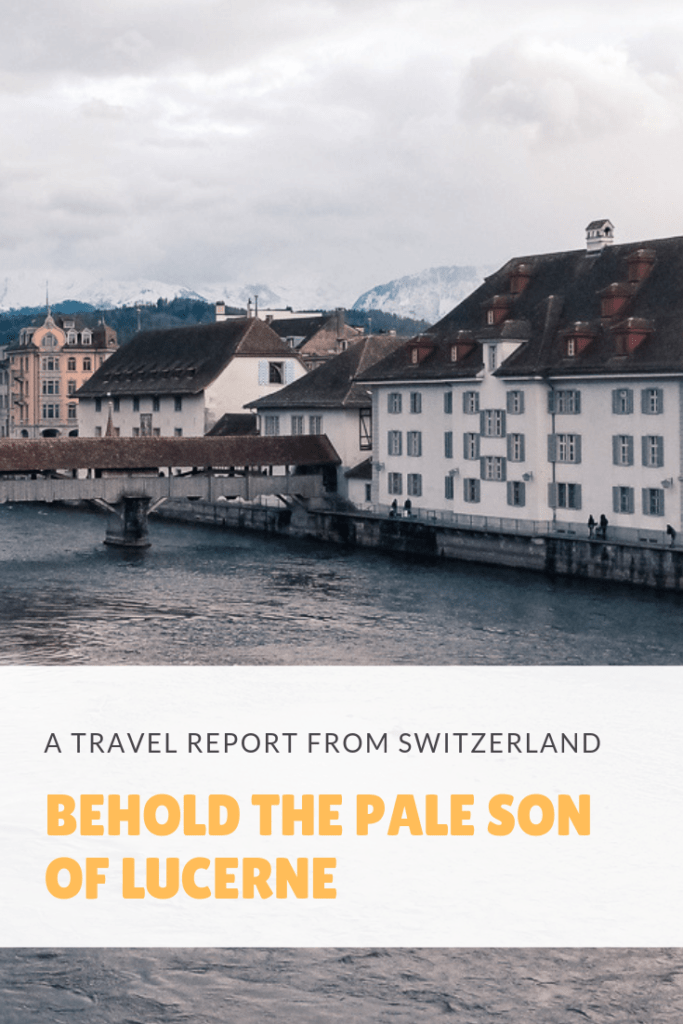

Lucerne has numerous bridges, but there is one that stands out from the crowd. The Kapellbrücke (Chapel Bridge) is the most renowned of them all, and it’s actually a missing element of this bridge that probably named the city. The bridge dates back from 1332, and it is 200 meters long. What makes it more special, though, is that midway into the water, it takes a turn and then continues towards the other side of Lucerne.

A real architectural gem, the Kapellbrücke features more than 100 triangular paintings from the early 16th century that narrate the city’s history. At some point across the river, there is a stone Watertower. This Watertower was probably used in former times as a Lucerna, a lighthouse. That’s probably where the city’s name comes from.

Equally impressive is the Spreuerbrücke (Mill Bridge), constructed in the early 15th century. This bridge is a spectacle of its own: despite looking like a peaceful relic of the past, when you attempt to cross it, it becomes something different: a memento mori statement. You will see skeletons and all sorts of death messages painted beneath its roof. That “Totentanz” or “Dance of Death,” painted by Kaspar Meglinger, serves as a reminder that no matter who you are, death will knock at your door. There are almost 70 paintings under the bridge, and in each one of them, you’ll see a skeleton representing death. He is here for everybody: ordinary people, monks, knights, a bride, a hunter, beggars, and, last but not least, the artist himself.

The contrast between the two bridges is remarkable: the Kapellbrücke and its lighthouse, and on the other hand, the Spreuerbrücke with the death messages. The two ancient motives of light and darkness co-exist in Lucerne. Two bridges exactly like two acrobats that love and hate each other.

A mournful lion in Lucerne

The more I dig, the more contrasts I find. I thought that Lucerne would be a prosperous and rather dull city, but the truth is it amazes me in every step I take.

Shortly before the entrance to the Gletschergarten, the city’s Ice Age remnant, there is a statue in front of a pond. It presents a lion with a sorrowful expression on its face. For a country like Switzerland, this seems to be a rather bizarre image. But whenever our perception fails to adapt to something, there comes History to offer a helping hand.

The Swiss Guards are famous worldwide, and even the guards protecting the Vatican come from Switzerland. Due to the fact that Switzerland is known for its political stability, it’s no surprise that the guards of Switzerland are among the most faithful. Back in 1792, when King Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette were trapped in the Tuileries Palace, 700 Swiss guards had to protect them. However, the anger of working-class Parisians was so intense that none of the guards survived. The guards paid their dedication with their lives: ironically, they didn’t know that the royal family had already escaped the palace…

In 1821, the Danish artist Bertel Thorvaldsen created a monument in remembrance of the fallen guards. The Löwendenkmal or “Lion Monument” stands on a sandstone. Above the lion, one can read: “HELVETIORUM FIDEI AC VIRTUTI,” which means “To the loyalty and bravery of the Swiss.”

At the end of the 19th century, Mark Twain made a stop in Lucerne. It was the time that he was writing his travelogue, A Tramp Abroad. Twain remained ecstatic in front of this monument due to the lion’s sorrowful expression. He described the Löwendenkmal as “the most mournful and moving piece of stone in the world.”

The Bourbaki Panorama

The Bourbaki Panorama is an impressive monument that portrays the internment of thousands of French soldiers who fled to Switzerland in the winter of 1871. The Panorama can be found in a beautiful building in the heart of Lucerne, and I come across it shortly after visiting the Löwendenkmal. It’s on the top floor, in a rotunda, and although it is also a sad story, it doesn’t feel mournful at all.

I stand in front of the Bourbaki Panorama, and I immerse myself in the Val-de-Travers valley at the end of the 19th century. In the Bourbaki Panorama, you will see a circular painting by Edouard Castres, which is 112 meters long and 15 meters high. The most impressive element is that it consists of a mixture of 3-dimensional visuals and 2-dimensional ones. That said, the borders between the dimensions are fragile.

I spend quite some time at the Bourbaki Panorama, which takes its name from a famous French General; his father was Greek, and the General was even proposed for the vacant Greek throne in 1872. Now and then, I walk around the Panorama, and I try to stand in a different spot each time. By looking at this legendary painting from every possible angle, I remember some past forms of narrative. The Bourbaki Panorama is a powerful representation of a world that nowadays seems distant. However, this sort of circular painting as a form is probably one of the predecessors of cinema.

Behold the pale son of Lucerne

This is exactly my kind of winter weather: extremely cold and sunny. I walk down the streets, and I often cross the bridges. This is an old habit of mine: the bridges make me feel temporarily like an acrobat. I love the idea, but I don’t think I could ever be one.

Bridge after bridge, I end up at the Seebrücke. It’s the modern bridge of Lucerne, and it usually has traffic. There are also lots of people walking on the pavements, and as I move towards the train station, I see a small crowd standing still. They seem occupied by some spectacle because they don’t pay any attention to them. I, of course, decide to approach them.

There are more than ten people. They are faced towards the river, but they don’t look at the water. I see two policewomen on the very front of the group. And, in front of the policewomen, there is a swan.

The policewomen keep the crowd away. When I ask them what’s going on, they explain to me that the swan is probably injured. They don’t know how, though. But what they know is that they have to protect the big waterbird until someone comes to take care of it. Meanwhile, the proud swan seems terrified. It looks unnatural that it doesn’t glide over the water and just perches on the busy bridge.

I’m glad it doesn’t sing.

The internal monologues of Lucerne

My days in Lucerne feel exactly like a circular painting; they start on the balcony and finish on the balcony. That’s the connecting point, that’s where the experience of the day seems to capitalize. I hear the Reuss river flowing: when I am on the balcony, it sounds almost like a torrent; when I’m in the room, it sounds like heavy rain.

This is my last night in Lucerne, and I think of Guillaume Apollinaire. In fact, his poem Zone comes to my mind. There, he describes the Eiffel Tower as a shepherd, and all the bridges of Paris resemble sheep. “In the end, you’re tired of this old world,” is the mind-blowing opening line. But tonight, I’m not tired of those old stories, of the aged houses or the sound of the river. On the contrary, I feel thirsty for more.

I then remember the famous Swiss poet Carl Spitteler, born in Liestal but died in Lucerne. I can still recall some of the internal monologues in his autobiographical novella Imago. If I had to visualize Lucerne metaphorically, then I would pick Spitteler. His face always seemed pale to me, and, of course, I remember once again the above-mentioned Apollinaire’s poem: “Behold the pale son and scarlet of the dolorous Mother.” Tonight, listening to the river’s torrential flow, I think that Lucerne dictates those internal monologues. It’s not an introverted place, but it feels like a very thoughtful one.

Love,

George

More about Switzerland: The mirrors of Zurich & What happens in Winterthur stays in Sankt Gallen

Please share, tweet, and pin if you enjoyed reading Behold the pale son of Lucerne. Your support keeps this website running and all the info up-to-date. 🙂

Last Updated on November 11, 2020 by George Pavlopoulos

No Comment