Last Updated on October 2, 2024 by George Pavlopoulos

Dear Barbara,

Hochlaki beach roars with ancient fury. This black-stoned beach seems to have existed before Nisyros itself. Here, you will always see waves. The stones are dragged back and forth, and the clamor never stops. The voice of the sea seems to emerge from the bowels of the volcano to narrate a modern sin: being happy at the edge of the sea when daily life wants to destroy you.

At one end, where the pavement turns and the beach unfolds for the first time, the municipality has dug a concrete shed into the rock. A retired couple finds shelter for a rare cigarette. They share it like somebody shares a plate of food or a holiday bed. They speak in low voices, but the sea drowns out the vowels. All that remains are the joints of the language, the consonants, which are integrated into the landscape like passing gravel.

The rock above them is steep, and on top of it stands Panagia Spiliani. The monastery has the Hochlaki on its back, and the tired umbrellas on the black stones look like eyes dazzled by the immensity from above. Three young tourists ask, staggering left and right, how they can get across to Bodrum. They’re not drunk; they’re just ignorant of the rough terrain and can’t balance.

It’s surprising that they don’t ask an agency in Mandraki. As a beach whose charm is the doubt rather than the solution, they get an answer from an old woman. She has just come out of the sea and looks happy in her one-piece swimsuit: “But why do you want to leave this place?”

Of cats and volcanoes in Nisyros, Greece

The cats in Nisyros are self-sufficient. They don’t request games or food. They observe passers-by in Mandraki, lying in shadowy corners like ancient mermaids. These cats rarely roost by the sea. They look dazed by the dim light and enjoy an island that, without the volcano, would not exist and would not host them.

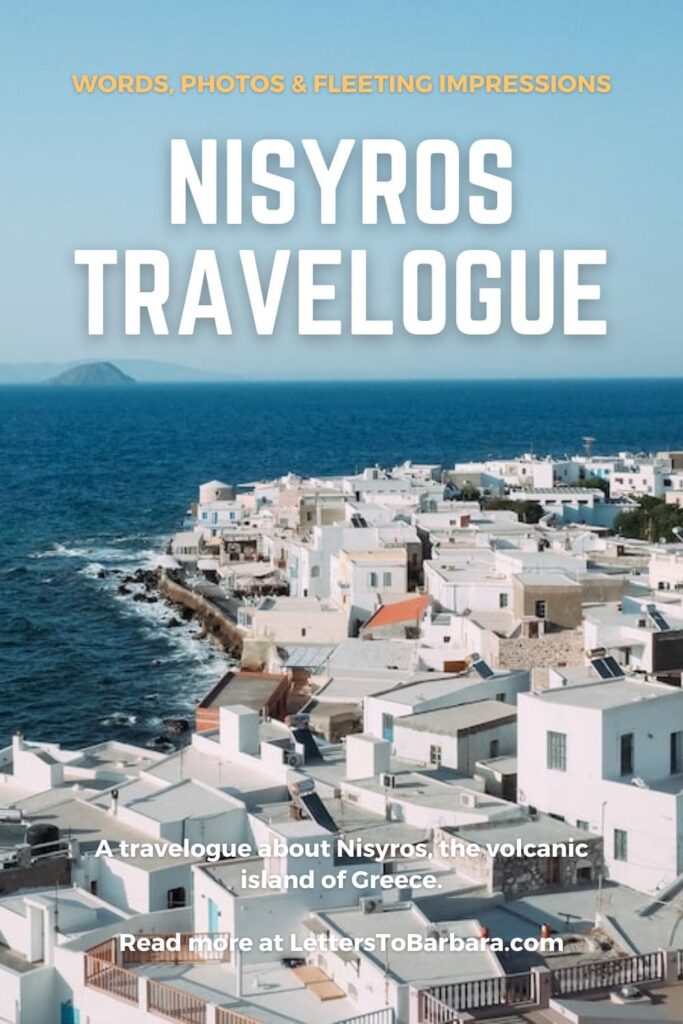

Mandraki is an enigmatic settlement. All its houses face the east to be protected from the constant west wind. They have two floors, and their thresholds are decorated with mosaics. Black and white pebbles, sometimes representing marine life and sometimes patterns, paint the courtyards. In the end, only one word is heard: “why?”

These black and white mosaics, which can also be found in the large squares of the island, look like a tribute to the materials of Nisyros. Images pop up every ten steps, just as the island once popped up. However, what matters here is not the technique but the symbolism: these artifacts are scattered around the courtyards of Nisyros like miniature volcanoes.

Absence and presence in Nisyros

The road that starts in front of Romanzo has a slight sulfur smell. It is a straight coastal road next to the wild sea. The turns are few but well-directed to reveal fragments of Yali. This nearby island with the sharp name -it means Glass– hosts workers who mine pumice every day. They leave at six in the morning and work under the merciless sun until three in the afternoon.

The slopes are green, and the cicadas are countless. As the road leads to Pali, the need to reach the end of the road becomes more intense. The dry rocks dwindle, and in the last turn before the big descent, the harbor appears calm, almost absorbed, like a reflection of eternal summer.

Pali resembles a movie scene: a street in front of the marina and behind the cluster of houses, a green slope. If someone walks fifty meters away from the harbor, he has the impression that the movie scene is over. The landscape is milder; perhaps the conversations in the seaside taverns have also tamed the sea, which here is shallow, ideal for children who are learning to dive and elderly people who are trying not to forget swimming.

The settlement is running out fast. Immediately after the beach, in the last house, two women talk every afternoon. They take out two plastic chairs on the asphalt and, impromptu, set up a terrace on the side of the road. The movement of cars becomes a topic of conversation, and as the summer heats up, the conversations multiply, like the waves on the back of the house.

One afternoon, a woman says: “They didn’t come this year.” No one knows whether she means her relatives from the States, a hypothetical number of tourists, or a flock of migratory birds that broke out en route from Africa.

Stand on your feet (again)

The small farm, where pigs are let out every noon, looks like a natural border. After carefully taking the turn, the green landscape ends abruptly. It only takes one more turn for the last trees to disappear and an almost Cycladic landscape to be seen.

Every time the goats hear a car, they run to hide on the yellow slopes among scattered stones. The trees become sporadic, lonely, as the deep sea dictates. And yet, not a single tree is superfluous in Nisyros. The weakest ones, those bent by the fury of the weather, are tied with ropes. Nisyros is a round pebble that teaches you to stand on your feet again.

Immediately after the Oasis tavern, the road ends, and all that remains is Lies and Pachia Ammos. It takes a quarter of an hour to walk over moving sand and under sculpted rocks to reach Pachia Ammos. Few beaches in the Aegean Sea can compare with this amphitheater cove. Hundreds of campers set up ephemeral accommodations by the sea. Every minor comfort in the sand seems like a distant luxury.

On some afternoons, the sandblasting is so strong that it feels like an indefinite punishment. If you don’t hide under an awning, the only refuge is Oasis, which is more than a tavern. It is an ode to the simplicity of food, to the Greek summer -while in need, it becomes a supermarket and a pharmacy for those camping under the relentless sun.

The windows of Nisyros

The sad Emporios and the floating Nikia are two windows overlooking the volcano.

Unseen from the sea, Emporios tries to resurrect itself. The 1933 earthquake and emigration have displaced the inhabitants, and revival is slow. High up, at the end of the hill, the Knights’ Castle is left looking out over the sea. Stops at the Balcony for delicious food and a view of the crater.

A few kilometers further, Nikia. All white, with an introverted square made for koukouzina and socializing. On a hidden ridge, wedged between rocks, a seismological station. And a little below, an inscription: “Good morning.” In all its majesty and vileness, the volcano below is ready to crush the island.

“Few houses means a bad village,” says Nikolas. A century of desolation on the caldera, without much hope for the future. People return sporadically, for a festival, for a memory, to open the shutters, and chase the winter away from the walls.

Wherever people leave, the experience becomes abstract.

The volcano of Nisyros

And, of course, there is the volcano of Nisyros itself.

The island’s bus has sacrificed routes to satisfy day-trippers arriving from Kos. Two itineraries all in all -the rest are for tourists. Every morning, sun-kissed crowds set off for five hours on the island. A stop at the volcano, a souvenir at Mandraki, and then back to the plastic sunbed.

But the volcano is worth seeing alone. Everything that exists before the birth of settlements and civilizations must be weighed with solitude as a measurement unit. The sea, the volcano, and the paths all are lost when city habits are established.

One afternoon, the road leads between the verdant slopes. In the final stretch, where the road flattens out, the trees begin to dwindle until they finally disappear. Only the yellow-streaked rocks and low vegetation remain, which is always underestimated.

After the tavern, the volcano of Nisyros. The crater, “Stefanos,” is bordered with stakes. Sulfur smells strong, but if you deceive the olfaction, you can say this unpleasant smell becomes almost charming. “Descend at your own risk,” warns the sign. However, the spectacle differentiates the meaning: the emphasis is on “descend,” not on “risk.”

The descent is like a slow lunar landing. Maybe this is what craters on the moon look like. The stakes gain height at every turn, but their styling seems meaningless. They delineate potentially dangerous tracks. Maybe hot water suddenly gushes out; maybe the ground is soft in some places. The heat from the sun on the face and the heat from the subsoil on the feet compose a yellow desert.

However, there is always room for mischief: the hand must rest within the fenced surface. The soil is soft, scalding like a piece of fresh bread. One feels the imperceptible roars of the volcano. The body, wrapped in sulfur and dust, becomes then a seismograph.

Solitude in the volcano, drunkenness from sulfur, and a crater that looks like it fell from the sky some ancient summer.

The horsemen of the night

In Mandraki, motorbikes descend the settlement at night with the engines off. They don’t turn on the lights to not worry the silver village. In fact, the riders are horsemen of the night, rolling through the streets like fallen knights on worn saddles. They pass like ghosts, silent and noble, searching for some vague port.

Only the waves can be heard on the small terrace at three in the morning. Four streets away from the sea, and yet, their sound reaches like a roar of lava that can’t sleep tonight. The celebration in the square is over, and the island is snoring lightly. The wind smells like fresh bread: a man stays up all night in a bakery.

Then, when the wind turns, a faint smell of sulfur coats Mandraki. This settlement at the mouth of the sea has a volcano at its back. It takes an explosion to turn the serenity into an untamed hell. The sea will then be the only escape route -but no one will part with Nisyros so easily.

Love always,

George

More about Nisyros: The ultimate Nisyros guide

Pin it for later

Sharing is caring. Share this Nisyros travelogue with your friends.