Dear Barbara,

This oval bay engulfs history and occupies one’s dreams. The serpentine promenade from La Concha to Zurriola is covered with earthly tones and materials that resist the salt and the wind. The Comb of the Wind isn’t just a sculptural project but a metaphor for San Sebastian: battling perpetually against the elements, natural and historical.

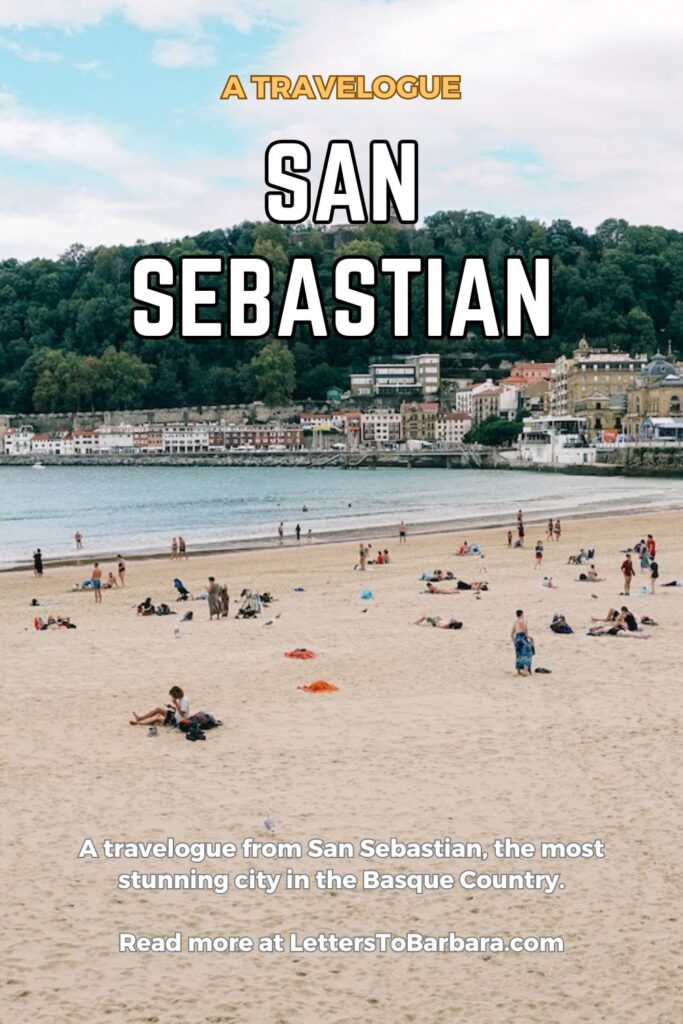

The city has itchy feet and a talkative mouth. It lies on the mouth of the Urumea River, and upon its wetlands, it has been built. One could find tons of analogies about this eternal flow. But the day I had the privilege to see San Sebastian for the first time, it was all about the Cantabrian Sea. La Concha is a poem in front of the Atlantic Ocean, and its verses are most likely the colorful figures walking on the sand.

It’s late autumn, and San Sebastian’s poetry unfolds like a bertso. Those long improvisational poems derive from the territory’s history. Seeing all these figures living life and speaking words before the low waves makes me think of Bilintx. One of the most iconic bertsolaris for the Basque, Bilintx lived, suffered, and died in the region.

One should observe how La Concha swallows the voices, absorbs them, and transforms them into waves. Unlike Odessa, in San Sebastian, the poem still unfolds. It feels like a scenographer built this city, then went on a walk and became a grain of sand at Pasealeku Berria.

The nudes of San Sebastian

The ocean is always cold. Apart from a courageous body, you need a certain mindset to jump into the water. All along La Concha, you can find spots for a quick dip into the open sea. The ocean isn’t just cold; it can be ruthless. However, on that privileged day, the sea is quiet, and the currents are sleepy. Still, only the brave take the opportunity.

A couple of months before my visit, I came across the paintings of Joaquín Sorolla. I remember the vivid colors and the portrayal of the sea. And now, as I stand behind the ornamented beach railings, I see something that resembles his paintings. I’m not aware if he ever painted nudes, maybe it was against the spirit of his era.

But here’s a sequence of ladies removing their clothes and jumping into the water. As if they are forever carved on the landscape, they naturally remove their clothes and, one by one, start swimming. One needs to turn his head to the other side, and that’s not just with respect to a private moment. It’s because those moments under the everchanging skies of San Sebastian must remain fragmented and vague like in a Sorolla painting.

Bullring in San Sebastian

It’s a tough call to leave the promenade behind. But I’m for the day in San Sebastian and I need to explore it. As I walk towards the city’s inner part, I feel melancholic: I have just a few hours left in town. I’m puzzled: Shall I see as much as possible, or should I just find a place to enjoy pintxos and rioja?

Tough dilemmas. The decision is to carry on walking, and I know I have to see the Constitution Square. What defines a progressive city is how it rethinks of itself, how it finds different usages to existing locations, and how the locals reinvent such spots. To evolve doesn’t quite often translate to adapt. But seeing a bullring converted into a square is unique.

The fire of 1813 destroyed the city. But the plan was there, the faith in the city, too. In 1817, the Constitution Square was constructed. Here, each window has a number. The square was an arena for bullfights; the numbers indicate bullring boxes from which you could watch the fight.

I walk around the square, trying to see if the faces have the thirst of a spectator. I curiously wonder if an old arena can still affect expressions or add at least a smirk of expectancy on people’s skin. The reply is far from affirmative.

A moment later, a man enters the square from the northeast side. He swears a lot. He probably stepped on something -an ice cream? The leftovers of a pintxo?- and stops. It’s something on the sole of his right shoe. And then, as if the old usage of the square returns, he stands on his left foot and rubs back and forth his right shoe several times, plenty of times, enough to resemble a bull.

Afterward, he just crosses diagonally the square and returns to the usage of the 21st century.

Santa Clara Island

And then it’s Santa Clara. As if San Sebastian doesn’t have enough beauty, a tiny island lies opposite the city. Santa Clara is the pearl of the bay of Donostia, and the small boat drives around the clock to its shore.

There’s a deserted lighthouse and tons of wild species on its soil. There’s something eerie in the atmosphere, though. Spots of reflection can also serve as places of isolation. In the late 16th century, the plague outbreak devastated the city. Santa Clara was used as a quarantine station for the infected. Preventing a disease wasn’t an easy task, and the tiny island saw death but also other people surviving on the other side of the bay.

Nowadays, there’s a bar, a beach affected by the tide, and loads of people searching for a quiet spot. An older lady on the boat tries to offer some insights about the island. She doesn’t speak English, and I don’t speak Spanish. Soon, this failed chat ends. We keep nodding to each other when something appears on the island—a human, a bird, a landscape.

We seem like two old friends who lost contact and have nothing more to say. Eerie places, eerie unspoken words until the waves push us back to San Sebastian.

The rain in San Sebastian

It now rains in San Sebastian. There’s no shelter all along La Concha -in fact, the shelter is the sea. Santa Clara disappears behind a light blanket of clouds, and the waterfront gets quickly deserted. I thought I’d never leave San Sebastian, that I’d stay here and become a detail in the landscape or at least a grain of sand somewhere along the promenade. But here I am, rushing to the bus station along elegant streets and a flamboyant Basilica.

I’m five minutes away from the station, and I have an urge to throw my ticket in the first dustbin and stay overnight. In reality, I want to throw that ticket and stay in San Sebastian without any plan to return. Travel writers often crave to change their lives, change their surname, and start fresh from a place that soothed their existence for a few hours. The more I think about it, the closer I am to deciding it.

But I’m now on the bus to Bilbao and writing you this letter. It won’t happen this time. But at least I know that if I ever want to change everything, I will most likely have to travel back to San Sebastian. And what a liberating thought that is.

Love,

George

More about the Basque Country: Getxo guide, Mundaka guide, Athletic Bilbao VIP experience, San Juan de Gaztelugatxe

Pin it for later

Sharing is caring. Share this San Sebastian travelogue with your friends.

Last Updated on February 15, 2025 by George Pavlopoulos