Dear Barbara,

I had no idea what to expect the moment I crossed the river Dniester. You see, Transnistria (or Pridnestrovie) is a narrow strip of land squeezed between Moldova and Ukraine. Most people have never heard of it. It is a self-proclaimed state that declared independence in 1992 after a short war against Moldova. An interesting fact about Transnistria is that no official country in the world recognizes its existence. The inhabitants pay in local roubles that have no value outside the country and won’t be exchanged elsewhere. For the majority of people, Transnistria is a country that doesn’t exist.

The capital city is Tiraspol and lies some 70 kilometers away from Chisinau. The infrastructure is in decay, and the road to Transnistria is full of snow. It seems that a big part of agricultural life has stopped, and the streets are empty. It’s very rare to see a car driving by, and the only constant motive apart from the snow is some white stones with a red top, counting the distance from Chisinau. All I see is a cluster of trees on both sides of the road and behind them, an all-white landscape that blends with the horizon somewhere in the distance, hazily.

Transnistria border crossing

At first, I see an empty outpost, serving like a notice that I’m about to enter Transnistria. Then there is a second one, where the guard asks for a quick check of my passport before nodding that I should carry on. And finally, after crossing the river Dniester, which is vast and partly frozen, I see Transnistria’s borders.

There is a tank blocking the street, and armed guards surround the vehicle. Two wild dogs bark at all times, which seems to be a prelude to a country that doesn’t exist. I see a couple of shacks behind the tank: on the first one, the officials check the passports, on the second one, the 10-hour visa is issued, while on the third one, a bureaucratic process that I fail to understand takes place. Whenever there is complete and utter confusion, the polite soldier passes me his smartphone. I have to write down the words that confuse him, and he then uses an online dictionary to translate them. In this shack, the most spacious of them all, I see posters of social realism and stickers of Transnistria’s flag with the hammer and sickle.

After almost twenty minutes, I have the visa in hand, and I exit the shack. It’s insanely cold, approximately -20 Celsius. I try to talk to one of the soldiers in English, but unfortunately, he doesn’t understand. “Very cold,” I just say. He then points his rifle towards the sky and replies: “But today, sun.”

Exploring Tiraspol, the capital of Transnistria

Tiraspol is a city of one hundred and thirty thousand inhabitants, and it takes about fifteen minutes by car to reach it after crossing the border of Transnistria. The first buildings that I see are gas stations and supermarkets. A company runs the biggest part of the commerce in Transnistria; its name is Sheriff. This is definitely an odd, almost Orwellian name. Sheriff owns a television channel, a construction company, several publications, a factory producing alcoholic drinks, the bread factory, a cell phone provider, and, of course, the local football club F.C. Sheriff.

One should never underestimate the power of a football club: F.C. Sheriff is Transnistria’s way to advertise the country to the rest of the world. Meanwhile, the Sheriff company itself has a significant influence on the local Parliament. Sheriff’s members hold top positions in the Transnistrian Parliament, while its leadership is often facing allegations of manipulating a coup d’ état.

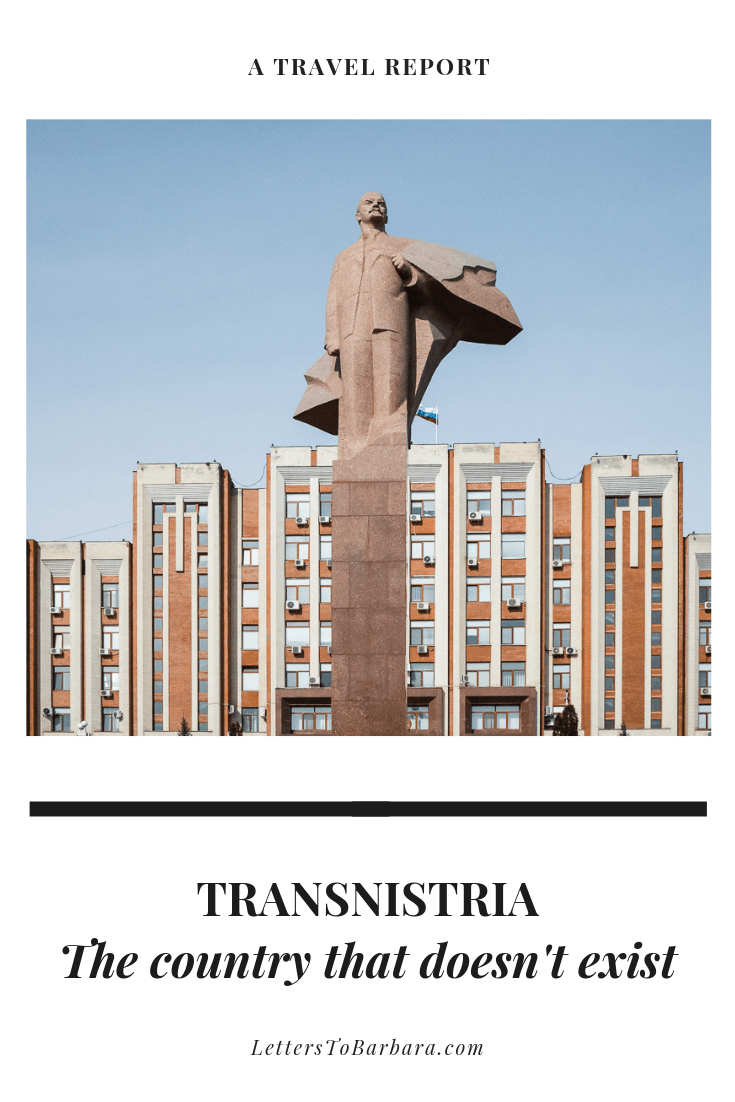

It’s not, of course, a big surprise that when I reach Tiraspol, the first building that I see is the Transnistrian Parliament. Lenin’s statue stands in front of the building in a victorious pose. Although I’m advised -like in Belarus– not to take photos of public buildings because I might be suspected as a spy, I cannot resist temptation. Indeed, I shoot a couple of images quickly. The city itself seems to be living in an old version of the Soviet Union. Whenever I ask someone in Tiraspol, using basic English, if he or she feels closer to Moldova or Russia, the answer is always the same: Russia, of course.

Close to the Parliament of Transnistria, I see the statue of Alexander Suvorov. He was a military leader and of the greatest national heroes. Despite the extreme cold, several kids are playing around this statue. The Transnistrian flag waves several meters above their heads. I have no idea if this is my first real image from Transnistria or if it’s just a cliché. But seeing those kids playing reminds me that, no matter how far you travel, all the essential elements of society remain intact.

The essence of Transnistria (Pridnestrovie)

How do you feel when you visit a country that doesn’t exist? Sometimes I have the feeling that I’m not really there, that everything is some sort of a movie set. Is this a travel paradox? No. Sovereign states are a norm dictated by international treaties and diplomacy. Although these norms affect our perception of reality, what really matters is what you see in the places you visit.

And yet, after exiting a supermarket, I meet a local that speaks adequate English. He is the guard of a Sheriff’s supermarket in downtown Tiraspol. Although his English is excellent, he feels a bit insecure. Exactly like the soldier in the shack, he has in hand his smartphone, and Google Translate is on. After talking with him for two or three minutes, he asks me where do I come from. When I reply, “from Greece,” he says: “Did you know that the name Tiraspol derives from Greek? ‘Tiras’ is the name of the river Dniester in ancient Greek and, of course, ‘Polis,’ which means “city” in Greek.” He has never visited Greece, but he says he would love to. He has lived his whole life here in Tiraspol, in the very same apartment block.

Most of the apartment blocks here are also monstrous, like in Chisinau. Huge cement boxes with small windows and a tired feeling occupy the biggest part of Tiraspol. But there is an essence of revolution in the streets that gives some breathing space to the city. Some of the most significant avenues are really wide; they have more than six lanes, while their names are dedicated to leaders and rebels of the Left. Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, to name but a few. To my surprise, the billboards are extremely popular here, reminding me of former times’ marketing techniques. There are large advertisements for cigarettes, but also messages about the quality of life in Tiraspol. The goal seems obvious, though: to lift the local morale.

Although it is a very sunny day, the temperature is several degrees below zero. There is just a handful of people in the streets. Most of them are kids, running and playing with the snow after school, and only rarely I see some older people, usually walking with grocery bags in hand. It’s only when I find myself once again in front of the Suvorov statue that I see some more people. About thirty faces are waiting stoically for the bus. This is the Avenue of the October Revolution, and a few street vendors advertise their merchandise. It doesn’t seem to be enough demand, though: handmade objects and past ornaments that no one really needs.

Hooked in Transnistria

I keep on walking in Tiraspol, but I guess that I have to find a café soon. The cold is, unfortunately, unbearable. But first, I have to help an old lady.

She stands in front of a store, and she asks me politely to help her. But the problem is that she only speaks Russian. Soon enough, the conversation turns to some kind of street theater: pantomime. She has a big hook in hand, and after a short introduction, she hands it over to me. I have no idea what to do with the hook. Soon, a bunch of people appears out of nowhere and observes the scene. The pantomime goes wrong, and the people around me start to laugh. I laugh, too. Then, she points her finger towards me: she shows me that I’m tall, and then she points to the “spectators” and makes a movement with her palm to show me they are short. Once again, everybody laughs.

The old lady wants me to fit the hook inside a ring to close her store’s roller shutter. The ring is on the top of the storefront, and from what I understand, the hook has just fallen. After a couple of attempts, I finally manage to hang the hook. The old lady seems grateful. She then holds my hands, and she starts talking to me for two minutes in Russian. I can’t understand what she says, it’s either her way to thank me, or she merely narrates a story. But in the end, she says, “thank you,” and she lets me go.

A café about love in Tiraspol

I have randomly heard about Love café. A couple talked about it at a bus stop: among Russian words, they always repeat the name Love café. I only have three hours before my visa expires, and I search on the map for the Love café. Due to the limited time I have in Transnistria, I didn’t manage to visit the Kvint distillery. The building is somewhere in Tiraspol’s outskirts, and from what I’ve read, it produces one of the finest cognacs in the world. If I’m lucky enough, though, I might have the chance to drink a glass at the Love café.

I walk down Lenin Street. Adjacent to a huge apartment block, I see the windows of the café: it seems to be the café of a post-apocalyptic world. It has two big windows, the facade is green, and naked showroom dolls are sitting on the roof. But this is just an impression from the exterior because when I enter the café, I realize that the decoration is pretty compatible with the name. Neo-romantic furniture, transparent curtains, and objects referring to -what else?- love.

When I’m about to order, though, I have to go through some kind of matching. The waitress gives me a menu in English, but she speaks only Russian. I show her what I’d like to order -focaccia with mushrooms- and she then searches for the dish on the Russian menu. Then, I point my finger to the cognac, and she once again certifies the order. Afterward, she goes through the Russian menu and proposes one more dish. It’s a local recipe that resembles croquettes. I nod affirmatively.

The Kvint cognac is indeed excellent. It also helps me to warm up a bit, and I can soon feel my face burning. Half an hour later, after soaking the sun that comes straight to the window, the waitress brings the focaccia and the croquettes. The food is delicious, exactly like in Moldova. It’s warm, it’s cozy, but above all, it is interesting here in Tiraspol. For a couple of minutes, I even think of extending my visa for Transnistria. There are a few hotels in Tiraspol, and I could stay here tonight. Unfortunately, it’s too late: the offices dealing with such requests aren’t open anymore.

After leaving the Love café, the sun has already started to set, and the cold seems even more severe. Tiraspol’s last image is a big building on the Avenue of the October Revolution with the letters Kvint on the roof. Kvint is a Russian acronym that stands for “Divine Wines and Beverages of Tiraspol.”

A must-have souvenir from Transnistria

There is not so much time left before my visa for Transnistria expires. But still, I would love to visit the second largest city of Transnistria, Bender. It is significantly smaller than Tiraspol, of course, but it’s just a couple of kilometers away, and its landmark is an impressive fortress. However, the traffic is so heavy that I can only get a fleeting image of the fort when I finally reach Bender. All I actually see is a bunch of turrets, their roofs being red. I stay in the car, and I follow the fortress with my eyes until it disappears under a deep blue sunsetting sky.

The traffic is still heavy, and there is some queue at the border crossing of Transnistria. The cars move slowly, but the process of exiting Transnistria is definitely faster. I just wait in the car until the soldier nods to me to approach. Then, I give him my passport and the 10-hour visa. The soldier is probably bored and not really stern. I would love to have the visa as a souvenir, but I have no idea if he’ll give it back to me or if he’ll destroy it.

The soldier checks both the passport and the visa and nods quickly that everything is okay. Then, he gives me both documents back. I’m happy: I have just visited Transnistria, the country that doesn’t exist, and I have the souvenir that proves it.

For the next two kilometers, I see soldiers here and there and a couple of unmanned outposts. Exactly like when I entered Transnistria, the wild dogs are barking and jumping up and down. Then, all I see is snow-covered fields. The landscape has no life; it is a bleak area, there are only a few cars, and Transnistria stays behind. It is already dark when I reach Chisinau, and it has started to snow again.

I’ll write to you soon,

George

Book your hotel in Transnistria| Rent a car

More about Moldova: Cricova, the underground wine city

More odd stories: Chiatura in Georgia, Brest in Belarus & Katskhi Pillar

Please share, tweet, and pin if you enjoyed reading Transnistria, the country that doesn’t exist. Your support keeps this website running and all the info up-to-date. 🙂

Last Updated on April 10, 2021 by George Pavlopoulos

I have never visited Transnistria (I haven’t even heard of it) but I would love to! The place seems really bizarre and I think that I should add it on my bucket list. Great text and photos, George!

Thanks, Anna! Transnistria is a very interesting place. I hope I can return there soon for some more stories and photos 🙂